Today I Learned — 2026-02-13

Today, I read more than I wrote intentionally...

Table of Contents

1. Brick Update

Yesterday, I discussed my experience using Brick. Today, I thought of two use cases where it can help:

- Firms can use Brick to ensure employees don't access social-media apps while in the office; and

- Event organizers (like during a wedding) can restrict guests from accessing certain apps (like camera for filming)

It's kinda cool, but also scary at the same time: internal enforcement is what makes one feel they are in control.

2. AI and Legal Services

Yesterday, an article was published that argued that AI will not make legal services cheaper or more accessible: AI Won't Automatically Make Legal Services Cheaper.

The core idea is that while AI can make producing legal "outputs" (documents, filings, briefs) cheaper, this does not mean that it will translate to making legal "outcomes" (actually winning your case, closing a deal, protecting your rights) more accessible.

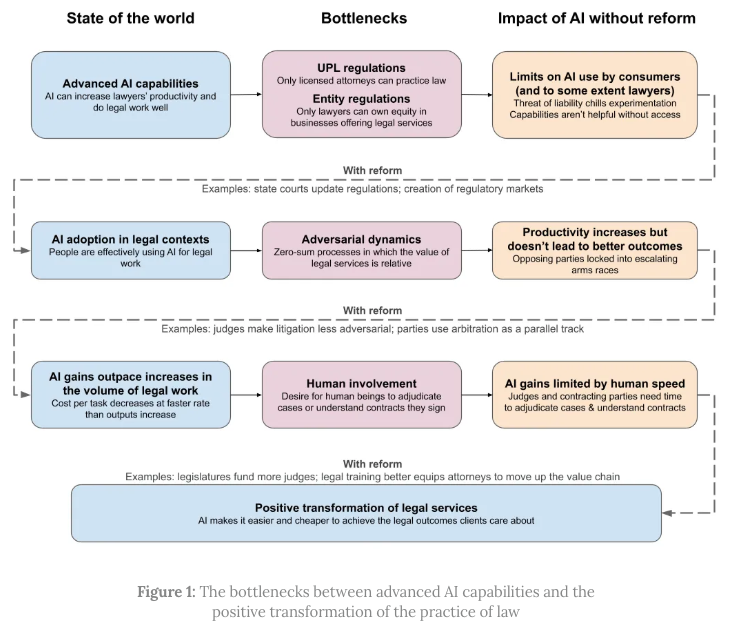

The authors argue that there are three bottlenecks standing in the way: regulatory barriers, adversarial dynamics, and human involvement. Here are the bottlenecks visualized:

2.1 Regulations Block AI from Helping People Directly

The authors fear two kinds of regulations: (1) UPL regulations; and (2) Entity regulations.

UPL stands for Unauthorized Practice of Law. It means that non-lawyers are not allowed to do legal work. Since AI isn't a lawyer, companies offering AI legal tools risk getting sued or fined. The authors cite two examples: (1) Upsolve; and (2) LegalZoom. Upsolve, a non-profit firm, tried to train volunteers to help people respond to debt collection lawsuits on a form (literally just checking boxes) as they might find difficulty understanding legal jargon. This got challenged at the court. LegalZoom, a company that automates rote tasks like paperwork, has been sued repeatedly for years over UPL.

Entity regulations restrict financing for AI companies offering legal services — only lawyers can own equity in such businesses. This can prevent tech companies from building more efficient legal service businesses.

Overall, the fear of these regulations can restrict user accessibility. However, the authors acknowledge that AI could reduce costs of legal services for reasons unrelated to its ability to perform legal tasks. For example, it could free lawyers by automating non-legal work, such as find and communicate with clients, manage administrative tasks, and handle payments, thereby, letting them spend more time on legal work.

2.2 Legal System is Competitive; AI Escalates Arms Race

The core issue here is that the American legal system is hyper-competitive and adversarial. Even if lawyers benefit from productivity gains by producing more legal "output", they are essentially competing with other lawyers who are also producing more legal "output". This can result in increase in legal "input" (like billable hours) and legal "output" (like contracts drafted, motions, filed, and briefs written) without corresponding legal "outcome", i.e., actually resolving the issue. Productivity gains can be absorbed by greater production. More billable hours and more work drafting documents may translate into greater revenue for legal firms without necessarily improving outcomes. The authors cite two examples for this: (1) Litigations; and (2) Transactional Work.

During litigation, one strategy is to increase the cost of the other side because "all things being equal, the party facing higher costs will settle on terms more favorable to the party facing lower costs." For example, discovery is a crucial phase during litigation that determines whether cases settle or go to train. One side can either "over-request" resulting in the other side having to review more documents, or the other side can "over-produce" burying the other side in a mountain of evidence. Even digitization has not helped in this regard, the authors claim. The authors shared several statistics, including "for every page eventually shown at trial, meaning it’s relevant and reliable enough to be used as evidence, over one thousand pages were produced in discovery."

Transactional work, such as negotiating and drafting contracts, is similarly adversarial. Lawyers on each side try to outmaneuver each other with contract language, and there's no natural limit to how much work you can throw at that. This has made contracts longer and more complex over time. The authors quote a statistics: "From 1996 to 2016, M&A agreements expanded from 35 to 88 single-spaced pages, their linguistic complexity increasing from post-graduate 'grade 20' to postdoctoral 'grade 30.'" However, the authors say that transactional work is less adversarial than litigation because contract negotiations take place before a dispute occurs.

2.3 Human Oversight

Even if AI can produce unlimited legal work instantly, humans still need to be involved. Judges need time to decide cases. Clients need time to understand contracts. If AI causes a flood of lawsuits (the authors estimate 2-5x more litigation), courts will either take longer to resolve cases (bad for everyone) or delegate to assistants and lower quality (also bad). Some courts dealing with debt collection cases already run "judgeless courtrooms" with lax standards. The authors argue we shouldn't replace human judges with AI either, for legal, technical, and moral reasons.

2.4 Reforms

Some reforms proposed by the authors:

- Create a new tier of legal service providers (like how nurse practitioners can do things previously reserved for doctors);

- Allow non-lawyers and companies to offer legal services under clear rules;

- Use "regulatory sandboxes" (Utah and Arizona are already testing this) where new business models can operate under modified rules while regulators study the impact;

- Make litigation less adversarial by borrowing from other countries' legal systems, like having courts appoint neutral expert witnesses instead of each side hiring their own;

- Expand the judiciary by hiring more judges;

- Allow AI-assisted arbitration as an alternative to traditional courts; and

- Rethink how lawyers are trained, since AI will automate entry-level tasks that junior lawyers currently learn from.

2.5 Thoughts

I am not a lawyer, so I can't evaluate what the authors are analyzing and proposing deeply. That said, it makes sense that there are structural barriers that won't just evaporate because AI models help translate and automate legal tasks. Yesterday, I discussed the HBR article which stated that AI will only intensify work. This also seems to apply here: increasing "inputs" and "outputs" for the lawyer may only intensify their work in the long run, especially in adversarial situations. Some of the reforms proposed by the authors seem aspirational ("hire more judges"). Other issues also apply to other industries like software ("automating entry-level tasks risk automating junior lawyers away"). Yet, other issues seem do-able, but will require work at the top (concerning regulatory frameworks).

All in all, I recommend diving deeper into the full article as it is copiously cited. I also need to read the reform sections a bit more carefully.